Insights

PFAS Update: State-By-State PFAS Drinking Water Standards - February 2023

Feb 21, 2023This blog was originally published in February 2023. Visit our up-to-date blog on PFAS drinking water standards: state-by-state regulations >

In the absence of an enforceable federal drinking water standard for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (“PFAS”), many states have started regulating PFAS compounds in drinking water. The result is a patchwork of regulations and standards of varying levels, which presents significant operational and compliance challenges to impacted industries. This client alert surveys the maximum contaminant levels (“MCLs”), as well as guidance and notification levels, for PFAS compounds – typically perfluorooctane sulfonate (“PFOS”) and perfluorooctanoic acid (”PFOA”) – in drinking water across the United States.

Federal Actions

There are two significant actions that the Federal Government has taken to establish requirements for certain PFAS substances.

Maximum Contaminant Levels

According to the PFAS Strategic Roadmap, EPA originally planned to issue proposed MCLs for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water by the end of 2022. Recently, EPA announced that the proposed listing will be released in March 2023, and the final regulation should be issued in September 2024, if not sooner.

This action will result in enforceable national drinking water standards for two PFAS compounds. A national drinking water limit will require drinking water systems across the entire country to evaluate the concentration of these two compounds in drinking water, and to implement treatment systems and permit limits to achieve the MCLs.

Health Advisory Levels

On June 15, 2022, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) issued four proposed health advisories (“HAs"). The values are as follows:

|

PFAS Substance |

Concentration |

|

PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic acid) |

0.004 ppt |

|

PFOS (Perfluorooctane sulfonate) |

0.02 ppt |

|

Gen X Chemicals (HFPO-DA) |

10 ppt |

|

PFBS (Perfluorobutane sulfonate) |

2,000 ppt |

The newly issued HAs for PFOA and PFOS supersede and dramatically reduce EPA’s 2016 Drinking Water Health Advisory Level of 70 ppt for PFOS and PFOA

EPA's HAs are non-enforceable, but are intended to provide technical information to state agencies and other public health officials regarding health effects, analytical methodologies, and treatment technologies associated with drinking water PFAS contamination.

For additional information, please refer to BCLP’s Client Alert regarding the new HA levels.

State Regulations

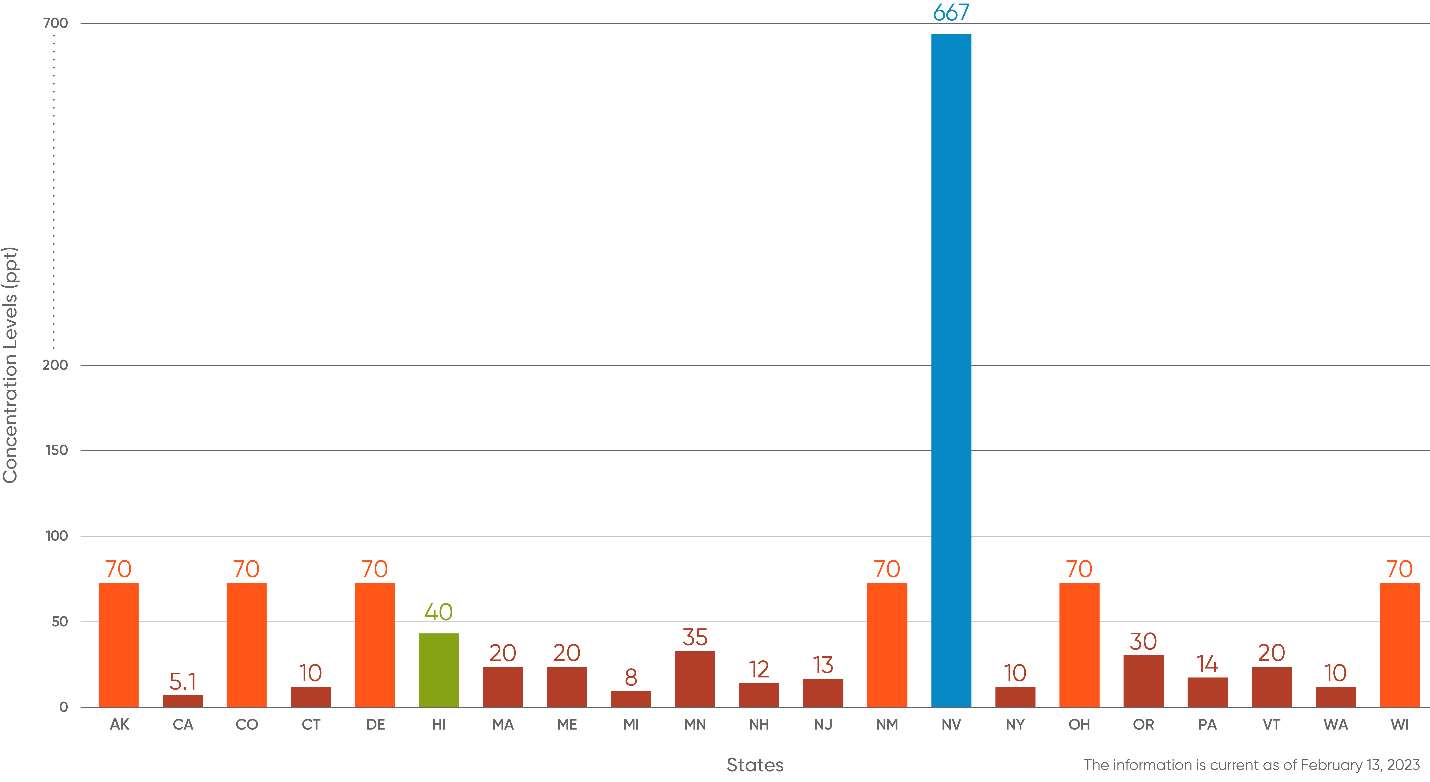

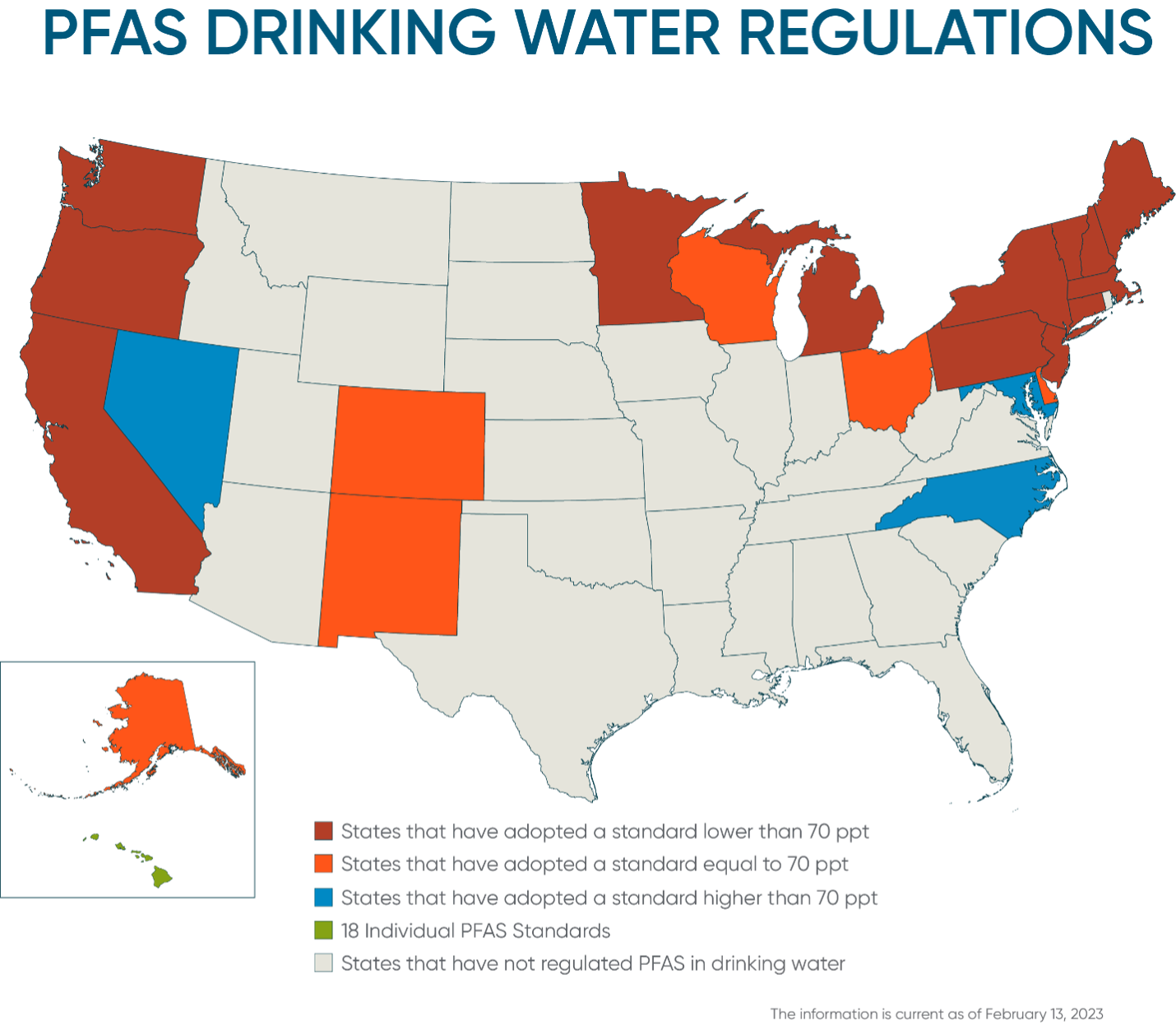

Until the federal government enacts final MCLs for PFOA and PFOS, the regulatory landscape for PFAS compounds in drinking water consists of an array of widely varying state-promulgated standards and regulations. For example, concentrations range from 3 ppt (California; PFHxA only) to 667,000 ppt (Nevada; PFBS only), depending on the PFAS compounds, the nature of the regulation, and the state’s view on which levels may result in health effects. The chart below illustrates the significance of the discrepancies between the regulatory levels for PFOA and/or PFOS.

The map and chart is current as of February 13, 2023, but this is a very active regulatory space, and significant state action is anticipated in 2023. For example, Delaware, Maine, Rhode Island, and Virginia have enacted legislation to establish MCLs for PFAS compounds for drinking water, so implementing regulations in those jurisdictions may be forthcoming. Additionally, numerous states, including Kentucky, have proposed, but not yet promulgated, drinking water regulations for PFAS.

Moreover, the New York Department of Health (“DOH”) proposed 10 ppt MCLs for four PFAS substances (PFDA, PFNA, PFHxS and PFHpA), along with a combined or aggregate MCL of 30 ppt for six PFAS substances (PFOA, PFOS, PFDA, PFNA, PFHxS and PFHpA).

Additionally, on November 15, 2022, a Michigan court invalidated that state’s seven PFAS drinking water MCLs, finding that the agency had not adequately explained its analysis of the cost impacts of the proposed law in the regulatory impact statement. The Michigan PFAS MCLs will remain in effect until the court issues a final judgment, but the decision highlights the tension between the regulatory intent and the resulting cost, and further litigation is expected as more states – and eventually the federal government - enact similar legislation.

|

|

Participating States |

Concentration Level |

Chemical(s) and Type of Regulation |

Regulatory Information |

|

|

California |

3 ppt |

PFHxS (Notification) |

|

|

|

California |

5.1 ppt |

PFOA (Notification) |

|

|

|

Michigan |

6 ppt |

PFNA (MCL) |

|

|

|

California |

6.5 ppt |

PFOS (Notification) |

|

|

|

Michigan |

8 ppt |

PFOA (MCL) |

|

|

|

Washington |

9 ppt |

PFNA (Notification) |

|

|

|

Connecticut |

10 ppt |

PFOS (Notification) |

|

|

|

Washington |

10 ppt |

PFOA (Notification) |

|

|

|

New York |

10 ppt |

PFOA and PFAS (MCL) |

|

|

|

New Hampshire |

11 ppt |

PFNA (MCL) |

|

|

|

Connecticut |

12 ppt |

PFNA (Notification) |

|

|

|

New Hampshire |

12 ppt |

PFOA (MCL) |

|

|

|

New Jersey |

13 ppt |

PFNA and PFOS (MCL) |

|

|

|

New Jersey |

14 ppt |

PFOA (MCL) |

|

|

|

Pennsylvania |

14 ppt |

PFOA (MCL) |

|

|

|

Minnesota |

15 ppt |

PFOS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

New Hampshire |

15 ppt |

PFOS (MCL) |

|

|

|

Washington |

15 ppt |

PFOS (Notification) |

|

|

|

Connecticut |

16 ppt |

PFOA (Notification) |

|

|

|

Michigan |

16 ppt |

PFOS (MCL) |

|

|

|

New Hampshire |

18 ppt |

PFHxS (MCL) |

|

|

|

Pennsylvania |

18 ppt |

PFOS (MCL) |

|

|

|

Massachusetts |

20 ppt (stated in the regulation as 20 ng/L) |

6 PFAS substances combined: PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpA, and PFDA (MCL) |

|

|

|

Vermont |

20 ppt (stated in the regulation as 0.000002 mg/L) |

5 PFAS substances combined: PFOA, PFOS, PFHpA, PFHxS, and PFNA (MCL) |

|

|

|

Maine |

20 ppt (stated in the Interim Drinking Water Standard as 20 ng/L) |

6 PFAS substances combined: PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpA, and PFDA (Notification) |

Interim Drinking Water Standard and Related Information |

|

|

Rhode Island |

20 ppt |

6 PFAS substances combined: PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpA, and PFDA (Notification) |

Interim Drinking Water Standard and Related Information |

|

|

Ohio |

21 ppt |

PFNA (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Oregon |

30 ppt |

4 PFAS substances combined: PFOS, PFOA PFHxS, and PFNA (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Minnesota |

35 ppt |

PFOA (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Hawaii |

40 ppt, etc.[1] (stated by the Hawaii Department of Health in µg/L) |

PFOA and PFOS; 16 other PFAS substances (Guidance) |

Environmental Action Levels (Table D-3a) |

|

|

Minnesota |

47 ppt |

PFHxS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Connecticut |

49 ppt |

PFHxS (Notification) |

|

|

|

Michigan |

51 ppt |

PFHxS (MCL) |

|

|

|

Washington |

65 ppt |

PFHxS (Notification) |

|

|

|

Colorado |

70 ppt (stated in the regulation as 70 ng/L) |

3 PFAS substances combined: PFOS, PFOA, and PFNA (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Alaska, Delaware, New Mexico, and Ohio |

70 ppt |

Adopted the EPA Standard: PFOS and PFOA combined (Notification and Guidance) |

Alaska: Action Level Delaware: Notification Policy New Mexico: Toxic Pollutant Standard |

|

|

Wisconsin |

70 ppt |

PFOS and PFOA combined (MCL) |

Regulation and Related Information |

|

|

Minnesota |

100 ppt |

PFBS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Ohio |

140 ppt |

PFHxS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Maryland |

140 ppt |

PFHxS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

North Carolina |

140 ppt |

GenX or HFPO-DA (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Minnesota |

200 ppt |

PFHxA (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Washington |

345 ppt |

PFBS (Notification) |

|

|

|

Michigan |

370 ppt |

Gen X or HFPO-DA (MCL) |

|

|

|

Michigan |

420 ppt |

PFBS (MCL) |

|

|

|

California |

500 ppt (stated in the regulation as 0.5 ppb) |

PFBS (Notification)

|

|

|

|

Nevada |

667 ppt (stated in the regulation as .667 µg/L) |

PFOA and PFOS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Colorado |

700 ppt (stated in the regulation as 700 ng/L) |

PFHxS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Ohio |

700 ppt |

Gen X or HFPO-DA (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Minnesota |

7,000 ppt |

PFBA (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Ohio |

140,000 ppt |

PFBS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Colorado |

400,000 ppt (stated in the regulation as 400,000 ng/L) |

PFBS (Guidance) |

|

|

|

Michigan |

400,000 ppt |

PFHxA (MCL) |

|

|

|

Nevada |

667,000 ppt (stated in the regulation as 667 µg/L) |

PFBS (Guidance) |

No PFAS drinking water regulations (as of the date of publication):

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming

Key:

|

Notification |

A corporate representative may have to inform an appropriate state official that a drinking water concentration in a water source owned or operated by the corporation (public well, supply tank, etc.) is above the limit. A water supply system also may have to inform its customers if there are any samples that exceed the PFAS values. |

|

Guidance |

The state establishes recommended concentration limits for one or more PFAS substances, but no notification or other action is required if concentrations exceed the recommended limits. |

|

MCL |

MCLs establish the maximum amount of a PFAS compound that can be present in drinking water. Treatment facilities that supply drinking water must ensure that these limits are met by treating and filtering the drinking water, and also by limiting the discharge of PFAS compounds through permits. |

How Do These Limits Impact Businesses?

MCLs set the maximum concentration of a given contaminant that can be present in drinking water. Drinking water systems are ultimately responsible for meeting the applicable MCLs and are required to ensure that drinking water distributed to the public meets these limits. State agencies often include discharge limits for drinking water sources to ensure that the drinking water provider can comply with the MCLs.

Businesses that currently or historically have used PFAS compounds, or have reason to believe that they may be present in their process wastewater effluent, should evaluate the following considerations:

- Whether their wastewater discharges, either directly or following treatment by the POTW or other treatment facilities, are eventually released to sources that are used for drinking water;

- Whether their discharge contains any of the PFAS compounds that are regulated in their jurisdiction; and

- Whether they are likely to be subject to permit conditions limiting the allowable concentration of PFAS compounds in their wastewater discharges.

Acquiring this information will allow businesses to determine whether they need to modify their operations to reduce or eliminate PFAS from their waste stream to achieve compliance with an existing standard, or in anticipation of likely future permit conditions.

Conclusion

The regulation of PFAS substances in drinking water will continue to develop over the next several years as additional research is conducted on potential health impacts, and as regulators at both the federal and state levels develop a deeper understanding of the prevalence of PFAS compounds in drinking water and the efficacy of different MCLs.

For more information on PFAS chemicals, and the regulatory and liability risks that they pose, please visit our PFAS webpage. If you have a question about how to manage PFAS risk in any jurisdiction, contact Tom Lee, John Kindschuh, Emma Cormier, or any other member of our PFAS team at Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP.

[1] Hawaii has 16 additional regulations, including the following: PFDA (.004 µg/L); PFNA (.0044 µg/L); PFUnDA (.01 µg/L); PFDoDA and PFTrDA (.013 µg/L); PFHxS (.019 µg/L); PFHpS and PFDS (.02 µg/L); PFOSA (.024 µg/L); PFHpA (.04 µg/L); PFTeDA (.13 µg/L); HFPO-DA (.16 µg/L); PFBS (.6 µg/L); PFPeA (.8 µg/L); PFHxA (4.0 µg/L ); and PFBA (7.6 µg/L).

Related Capabilities

-

PFAS

-

Environment