Insights

Navigating the Corporate Transparency Act maze: hidden pitfalls of employee structuring for the large operating company exemption

Jan 29, 2024Summary

With the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) now in effect, it is crucial for privately held mid-sized and large companies to look into and re-examine their corporate structures to ensure compliance with the new law. While the CTA primarily targets smaller companies in lightly regulated industries, larger companies should not automatically assume they and all of their affiliates are exempt from its reporting requirements. This is particularly true for those using common employee structures where employees are retained in separate subsidiaries or affiliates of a holding or operating company of the business. Such structures could inadvertently place the holding and operating companies, as well as their subsidiaries, under the ambit of CTA’s reporting requirements, underscoring the need for a comprehensive review of such businesses’ corporate and employment structures to ensure full compliance with the CTA. We will discuss the employee prong of the “large operating company” exemption in more detail below, with examples of how an organization’s structure might affect the analysis.

CTA and the Large Operating Company Exemption

Effective January 1, 2024, the CTA represents a significant shift in reporting requirements for legal entities formed under U.S. law and entities formed outside the U.S. and registered to do business in the U.S.[1]The CTA primarily targets small to mid-sized legal entities within lightly regulated or unregulated industries, mandating these entities, referred to as “Reporting Companies”, to disclose their beneficial ownership information. According to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), it is estimated that over 32 million existing entities will make initial reports in the first year of the CTA's effective date, with around 5 million new entities expected to report annually thereafter.

While the CTA casts a wide net, it also provides exemptions for certain categories of entities, most notably those that are larger and/or more heavily regulated by the U.S. government. There are 23 exemptions in total, with one key exemption being for “large operating companies.” Under the CTA, an exempt “large operating company” means any entity that meets ALL of the following criteria:[2]

- employs more than 20 employees on a full-time basis in the United States;

- has an operating presence at a physical office in the U.S.; and

- filed a U.S. federal income tax return or information return for the previous year demonstrating more than USD $5 million in gross receipts or sales, net of returns and allowances, excluding gross receipts or sales from sources outside the U.S. For purposes of this test, the entity must use a consolidated return amount if the entity filed a return as part of an “affiliated group of corporations” within the meaning of 26 U.S.C. § 1504.

This exemption also extends to subsidiaries “whose ownership interests are controlled or wholly owned, directly or indirectly” by a large operating company, though it notably does not apply to affiliates or parent companies of such exempt entities.

Navigating the Employment Aspect of the “Large Operating Company” Exemption

While those advising many mid-sized or large privately held companies might believe they can easily satisfy the criteria for a “large operating company” exemption under the CTA due to their substantial employee count and significant gross revenue, this may not necessarily be the case if those organizations employ a common structure where all of the employees are grouped as a legal matter in a separate subsidiary or affiliate leaving the holding and/or main operating company without at least 21 full-time employees as defined in the CTA and related regulations.

No Employee Aggregation Across Affiliated Entities

While revenue may be aggregated across subsidiaries to reach the required $5 million threshold for the purposes of a “large operating company” exemption, the employee headcount may not. In other words, each entity must have the required more than 20 full-time employees to qualify for the “large operating company” exemption. And while some commenters on the initial CTA rules proposal suggested that “the employee count should be evaluated on a consolidated basis, rather than on an entity-by-entity basis, to the extent the entity is part of a consolidated group,” this suggestion was not adopted.[3]As FinCEN noted in its rules’ Supplemental Release, this result with respect to employee count appears to have been a deliberate choice by Congress: “FinCEN declines to permit companies to consolidate employee headcount across affiliated entities. Although the CTA specifies that gross receipts or sales are to be consolidated, the CTA contains no similar specification for employee headcount. To the contrary, [the statute] provides that the exception applies to an ‘entity that… employs’ more than 20 employees, indicating that the determination of the number of employees is to be made on an entity-by-entity basis.”[4]

Narrow Meaning of a “Full-Time Employee”

Moreover, only full-time employees in the United States within the meaning provided in 26 C.F.R. § 54.4980H–1(a) and § 54.4980H–3 count toward the required more than 20 employees (except that the term “United States” for this purpose is the broader definition as provided in 31 C.F.R. § 1010.100(hhh), i.e. “States of the United States, the District of Columbia, the Indian lands (as that term is defined in the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act), and the Territories and Insular Possessions of the United States”).

In addressing how to determine who is a full-time employee, FinCEN noted in its rules’ Supplemental Release that “[t]he proposed rule borrowed familiar IRS concepts widely used by employers” for regulatory consistency and simplicity purposes. A full-time employee will generally be a person who is employed an average of at least 30 hours of service per week or 130 hours of service per month with the particular entity-employer, with certain adaptations for non-hourly employees. However, it is unclear whether any part-time employees could be included in this analysis.

Based on the references included in the Final Rule, it appears that “employee” status is to be determined under familiar common law standards. Thus, the employer should generally be the W-2 employer for this purpose, but note that in a number of common payroll arrangements the common-law employer may not be the same entity as the W-2 issuer, and it may even be unclear which entity is the common-law employer (e.g., in the case of common paymaster, employee leasing, employee sharing, or secondment arrangements).

The treatment of part-time employees and the common law employer analysis seem like areas that are ripe for FinCEN to address further in the future but to date it has not expressed a great deal of flexibility in this regard.

Continuous Monitoring Obligation

Finally, while some commenters to the initial CTA rules proposal noted that “the number of employees should be tied to a reference period, such as an average over the last year,” FinCEN made it clear that it expects companies to continuously monitor the headcount of their employees to evaluate whether the exemption applies to the entity. FinCEN rejected an average over time concept to determine the number of full-time employees as “such evaluations should be as simple as possible, and as consistent as possible from reporting company to reporting company.”[5] Thus, entities that are close to the 21 full-time employee threshold should carefully monitor the number to determine that the exemption still applies.

Popular Employment Structures and CTA Implications

Common organizational structures could inadvertently subject some or all of an organization’s entities to the CTA’s reporting obligations, challenging their initial assumption of exemption and necessitating a careful review of their organizational and employment practices. The following examples assume the subject companies otherwise satisfy the CTA’s threshold definition of “reporting companies” and illustrate common structures that implicate these principles.

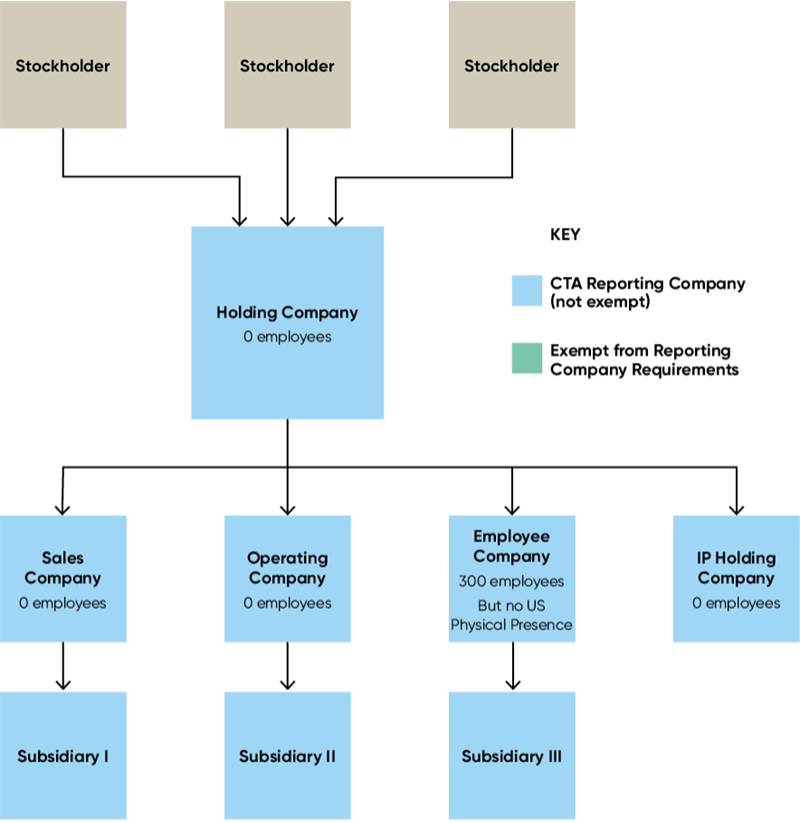

Example 1

In Example 1, the Holding Company does not have any employees, and all employees are employed by a subsidiary. The Holding Company and its subsidiaries would not qualify for the “large operating company” exemption even though its subsidiary Employee Company has well over 20 full-time employees. In this scenario, Employee Company does not have a U.S. physical operating presence (prong 2), so it does not qualify as a “large operating company” either. In this example, all of the entities in the structure are reporting companies under the CTA.

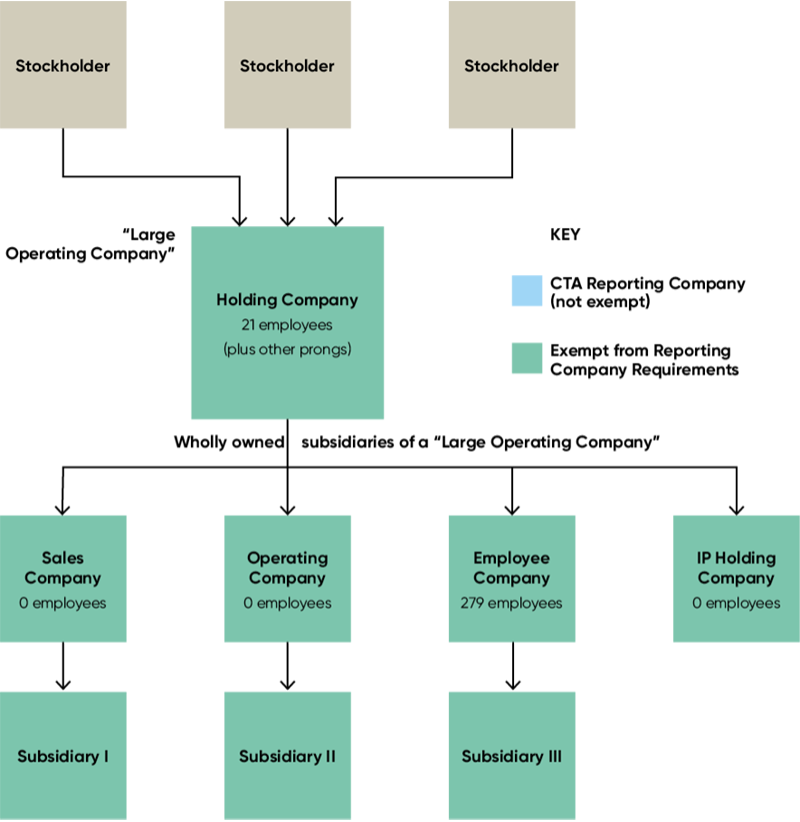

Example 2

In Example 2, the Holding Company has more than 20 full-time employees and meets the other prongs of the “large operating company” test. As long as it continues to meet all three prongs of the test, it would be exempt from reporting requirements under the CTA. All of its wholly owned subsidiaries would also be exempt as subsidiaries of a “large operating company.” If the Holding Company employed only 20 full-time employees because an employee left before a replacement was employed, the Holding Company and its subsidiaries would no longer be exempt.

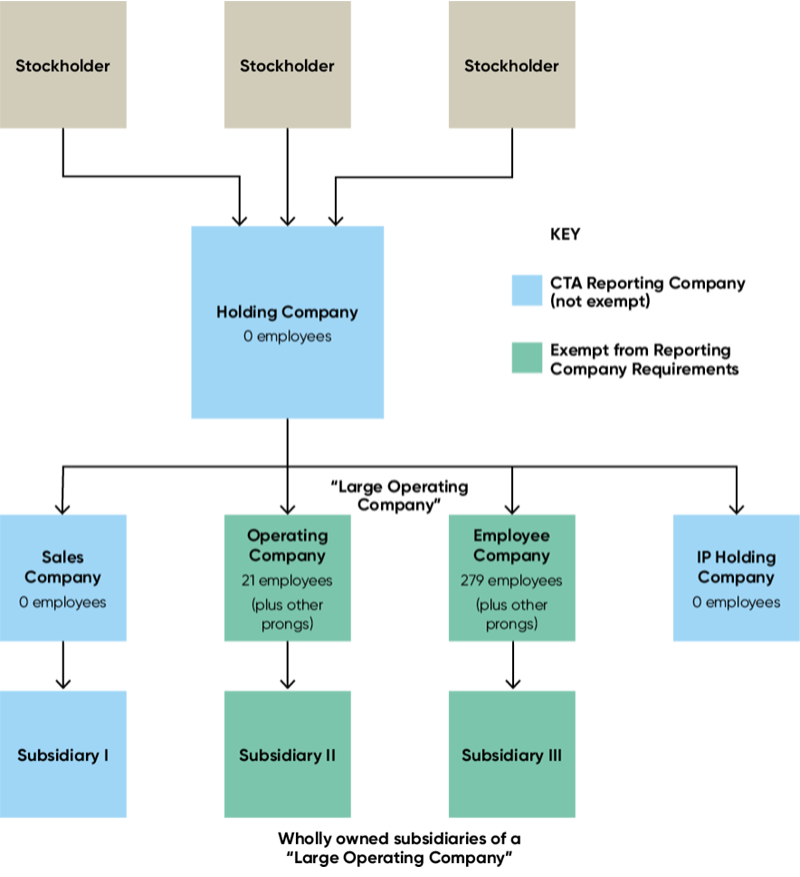

Example 3

In Example 3, the Holding Company does not have more than 20 full-time employees and it is a reporting company. The entities labelled as “Operating Company” and “Employee Company” under Holding Company would be exempt from reporting requirements as “large operating companies” and Subsidiary II and Subsidiary III would be exempt as wholly owned subsidiaries of large operating companies. As long as the Operating Company and Employee Company continue to meet all three prongs of the test, these four entities would be exempt from reporting requirements under the CTA. The other entities would still be considered CTA reporting companies.

Conclusion: Navigating the CTA’s Implications

The introduction of the CTA has significantly altered the compliance landscape for companies doing business in the U.S., including those that rely on subsidiary structures for managing their workforce. It is crucial for larger and more complex organizations, which might have assumed full exemption from the CTA’s scope, to undertake a thorough review of their organizational and employment structures. This review is essential to ensure that they meet the CTA’s stringent compliance standards. For many, this could mean having to report their beneficial ownership information or possibly restructuring their employment models to align with the CTA’s exemptions or reporting requirements. Of course, any restructuring for this purpose will have to be weighed in light of the potential tax and other advantages of their existing structure.

The complexity of the CTA and the severe implications of non-compliance underscore the necessity for businesses to seek expert legal advice. BCLP has established a cross-disciplinary team of lawyers from its corporate, litigation, private client, privacy, financial services regulatory, and other practice groups to support clients on CTA compliance matters. Our team assists clients in considering the availability of CTA exemptions, who should be identified as a company’s beneficial owners and applicants, what kind of information must be reported about them, the impact of the CTA on investment and management strategies and structures, and what CTA compliance policies and procedures should be adopted.

[1] 31 C.F.R. § 1010.380(c).

[2] 31 CFR § 1010.380(c)(2)(xxi).

[3] See 87 Fed. Reg. 59,542.

[4] 87 Fed. Reg. 59,543 (emphasis in original; footnotes omitted).

[5] 87 Fed. Reg. 59,543.

Related Practice Areas

-

Financial Regulation Compliance & Investigations