BCLPemerging.com

PFAS drinking water standards: state-by-state regulations

Updated: September 2024

Sep 13, 2024Summary

The regulation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (“PFAS”) in drinking water remains one of the primary focuses for legislatures and agencies at both the state and federal levels. In April 2024, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) issued Maximum Contaminant Levels (“MCLs”) and Maximum Concentration Level Goals (“MCLGs”) for certain PFAS, establishing limits as low as 4 parts per trillion (“ppt”). Many states have already regulated PFAS compounds in drinking water but have done so in a variety of different ways, and at different levels.

The result is a patchwork of regulations and standards which presents significant operational and compliance challenges to impacted drinking water systems. This client alert surveys the the MCLs, as well as guidance and notification levels, for PFAS compounds in drinking water across the United States.

Federal Actions

On April 10, 2024, the EPA issued a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (“NPDWR”) establishing MCLs and MCLGs for certain PFAS substances in drinking water. The applicable details are summarized below:

| Compound | MCLs (enforceable) | MCLGs (non-enforceable) |

| PFOA | 4.0 ppt | 0 (Zero) |

| PFOS | 4.0 ppt | 0 (Zero) |

| PFHxS | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| PFNA | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| HFPO-DA (known as GenX Chemicals) | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| Mixtures containing two or more of these four PFAS substances: PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS | 1 (unitless) Hazard Index |

1 (unitless) Hazard Index |

As discussed in more detail in our previous post, there are three aspects of EPA’s NPDWR that are particularly noteworthy:

- EPA decided to include four additional PFAS compounds beyond PFOA and PFOS, demonstrating that the agency’s focus extends beyond those two compounds.

- EPA’s 4 ppt MCLs for PFOA and PFOS are incredibly low, but the agency set the MCLGs for both compounds at zero and explained that EPA is allowing 4 ppt as the MCL because that is the lowest detection level that is generally achievable at commercial laboratories. EPA has indicated that it will continue to reduce the MCLs for those two compounds as testing methodologies improve.

- Rather than establish simple numeric concentration limits for the four new PFAS compounds, EPA implemented a Hazard Index (“HI”) approach for all four compounds combined. EPA used the HI based on its conclusion that PFAS compounds are often commingled and that can result in an additive health impact. While not unprecedented, this HI approach will create challenges as water systems try to implement testing and controls to try to meet these standards.

For additional information, please refer to EPA’s NPDWR website and the final rule in the Federal Register.

State Regulations

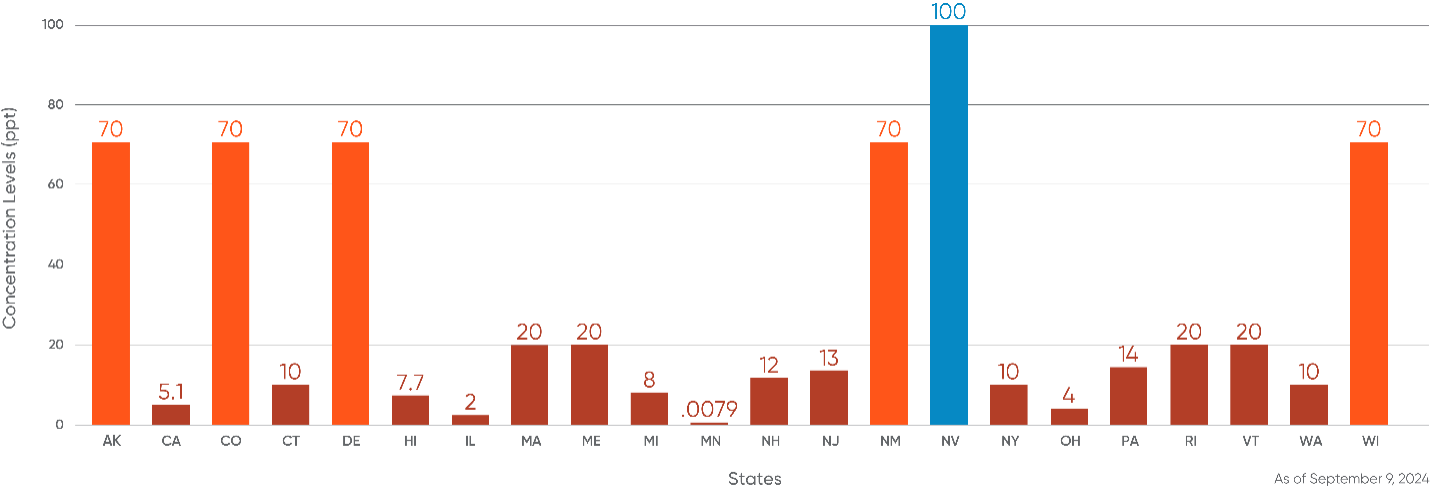

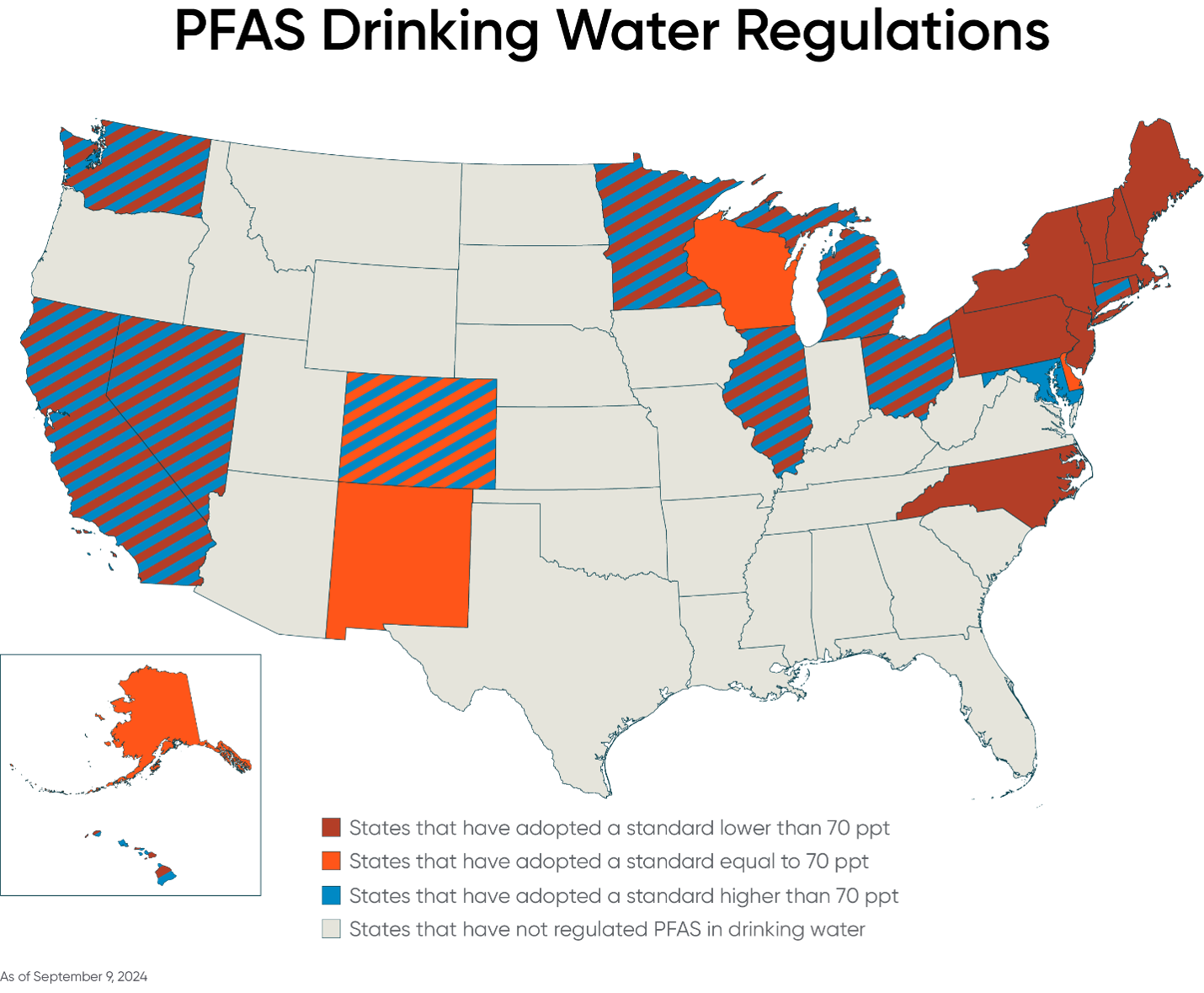

The regulatory landscape for PFAS compounds in drinking water at the state level currently consists of an array of widely varying standards and regulations. For example, concentrations range from 0.0079 ppt (Minnesota; PFOA only) to 400,000 ppt (Michigan; PFHxA only), depending on the PFAS compounds, the nature of the regulation, and the state’s determination as to which levels may result in health effects. The chart below illustrates the discrepancies between the regulatory levels for PFOA and/or PFOS.

The map and chart are current as of September 9, 2024, but this is a very active regulatory space, and additional state action is anticipated soon. For example, Delaware and Virginia have enacted legislation to establish MCLs for PFAS compounds for drinking water, so implementing regulations in those jurisdictions may be forthcoming. Additionally, several states, including Minnesota, North Carolina I, North Carolina II, and South Carolina, have proposed, but not yet promulgated, various types of drinking water regulations for PFAS.

Notably, proposed bills have been introduced in Maine and New York mandating the testing of drinking water in private wells for several PFAS substances during property transactions. Additionally, some states, such as Oregon, are in the process of enacting laws that are consistent with the newly enacted federal requirements.

States that have adopted a standard lower than 70 ppt |

Concentration level

3 ppt (stated by the California Water Boards as 3 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (Notification)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

5.1 ppt (stated by the California Water Boards as 0.0000051 mg/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

6.5 ppt (stated by the California Water Boards as 0.0000065 mg/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

2 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

6:2 chloropolyfluoroether sulfonic acid (Notification)

Regulatory information

Action Level and related information

Concentration level

5 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

8:2 chloropolyfluoroether sulfonic acid (Notification)

Regulatory information

Action Level and related information

Concentration level

10 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS (Notification)

Regulatory information

Action Level and related information

Concentration level

12 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFNA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Action Level and related information

Concentration level

16 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Action Level and related information

Concentration level

19 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

Gen X or HFPO-DA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Action Level and related information

Concentration level

49 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

7.7 ppt, etc.[1] (stated by the Hawaii Department of Health as 0.0077 µg/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS and 19 other PFAS substances (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Environmental Action Levels (Table D-3a)

[1] Hawaii has 19 additional regulations, including the following: PFDA (7.7 ppt); PFOA, HFPO-DA, and PFNA (12 ppt); PFUnDA (19 ppt); PFDoDA and PFTrDA (26 ppt); PFHpS and PFDS (38 ppt); PFOSA (46 ppt); PFHpA and PFHxS (77 ppt); PFTeDA (260 ppt); ADONA (1,200 ppt); PFPeA and 6:2 FTS (1,500 ppt); PFBS (1,700 ppt); PFHxA (1,900 ppt); and PFBA (15,000 ppt).

Concentration level

2 ppt (stated by the Illinois Environmental Pollution Control Agency as 2 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

14 ppt (stated by the Illinois Environmental Pollution Control Agency as 14 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

21 ppt (stated by the Illinois Environmental Pollution Control Agency as 21 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFNA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

20 ppt (stated in the Interim Drinking Water Standard as 20 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

6 PFAS substances combined: PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpA, and PFDA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

20 ppt (stated in the regulation as 20 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

6 PFAS substances combined: PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpA, and PFDA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

6 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFNA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

8 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

16 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

51 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (MCL)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

0.0079 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Health Advisory and related information

Concentration level

2.3 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Health Advisory and related information

Concentration level

47 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

6.67 ppt (stated by the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection as .0667 µg/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFSA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

10 ppt (stated by the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection as .1 µg/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

11 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFNA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

12 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

15 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

18 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (MCL)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

13 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFNA and PFOS (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

14 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

10 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA and PFAS (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

10 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

GenX or HFPO-DA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

4 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS and PFOA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

10 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS, PFNA, and Gen X (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

14 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

18 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS (MCL)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

20 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

6 PFAS substances combined: PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpA, and PFDA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

20 ppt (stated in the regulation as 0.000002 mg/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

5 PFAS substances combined: PFOA, PFOS, PFHpA, PFHxS, and PFNA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

9 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFNA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

10 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

15 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

65 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (Notification)

Regulatory information

States that have adopted a standard equal to 70 ppt |

Concentration level

70 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

5 PFAS substances combined: PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFHxS, and PFHpA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

70 ppt (stated in the regulation as 70 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

3 PFAS substances combined: PFOS, PFOA, and PFNA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

70 ppt but proposing new MCLs

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS and PFOA combined (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

70 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS, PFHxS and PFOA combined (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

70 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFOS and PFOA combined (MCL)

Regulatory information

States that have adopted a standard higher than 70 ppt |

Concentration level

500 ppt (stated (stated by the California Water Boards as as 0.0005 mg/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

700 ppt (stated in the regulation as 700 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Translation Level and related information

Concentration level

400,000 ppt (stated in the regulation as 400,000 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

240 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Action Level and related information

Concentration level

760 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Notification)

Regulatory information

Action Level and related information

Concentration level

1,800 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBA (Notification)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

140 ppt (stated by the Illinois Environmental Pollution Control Agency as 140 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

2,100 ppt (stated by the Illinois Environmental Pollution Control Agency as 2,100 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

3,500 ppt (stated by the Illinois Environmental Pollution Control Agency as 3,500 ng/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

140 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

370 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

Gen X or HFPO-DA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

420 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (MCL)

Regulatory information

Regulation and related information

Concentration level

400,000 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxA (MCL)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

100 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Health Advisory and related information

Concentration level

200 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFHxA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Health Advisory and related information

Concentration level

7,000 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBA (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

10,000 ppt (stated by the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection as 10 µg/L)

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

2,000 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

140,000 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Guidance)

Regulatory information

Concentration level

345 ppt

Chemical(s) and type of regulation

PFBS (Notification)

Regulatory information

Related information |

*as of date of publication

- Alabama

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- Florida

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- North Dakota

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Virginia

- West Virginia

- Wyoming

Notification

A corporate representative may have to inform an appropriate state official that a drinking water concentration in a water source owned or operated by the corporation (public well, supply tank, etc.) is above the limit. A water supply system also may have to inform its customers if there are any samples that exceed the PFAS values.

Guidance

The state establishes recommended concentration limits for one or more PFAS substances, but no notification or other action is required if concentrations exceed the recommended limits.

MCL

MCLs establish the maximum amount of a PFAS compound that can be present in drinking water. Treatment facilities that supply drinking water must ensure that these limits are met by treating and filtering the drinking water, and also by limiting the discharge of PFAS compounds through permits.

How Do These Limits Impact Businesses?

MCLs set the maximum concentration of a given contaminant that can be present in drinking water. Drinking water systems are ultimately responsible for meeting the applicable MCLs and are required to ensure that drinking water distributed to the public meets these limits. State agencies often include limits for discharges to drinking water sources to ensure that the drinking water provider can comply with the MCLs.

Businesses that currently or historically have used PFAS compounds, or have reason to believe that they may be present in their effluent, should evaluate:

- Whether their wastewater discharges, either directly or following treatment by the POTW or other treatment facilities, are eventually released to sources that are used for drinking water;

- Whether their discharge contains any of the PFAS compounds that are regulated in their jurisdiction; and

- Whether they are likely to be subject to permit conditions limiting the allowable concentration of PFAS compounds in their wastewater discharges.

Acquiring this information will allow businesses to determine whether they need to modify their operations to reduce or eliminate PFAS substances from their waste stream to achieve compliance with an existing standard, or in anticipation of likely future permit conditions.

Conclusion

The regulation of PFAS substances in drinking water will continue to develop over the next year as additional research is conducted on potential health impacts, and as regulators at both the federal and state levels develop a deeper understanding of the prevalence of PFAS compounds in drinking water and the efficacy of different MCLs.

For more information on PFAS chemicals, and the regulatory and liability risks that they pose, please visit our PFAS webpage. If you have a question about how to manage PFAS risk in any jurisdiction, contact Tom Lee, Bryan Keyt, Erin Brooks, John Kindschuh, or any other member of our PFAS team at BCLP.

Related Practice Areas

-

PFAS Team

-

Environment