BCLPemerging.com

2023 Federal PFAS Regulatory Recap

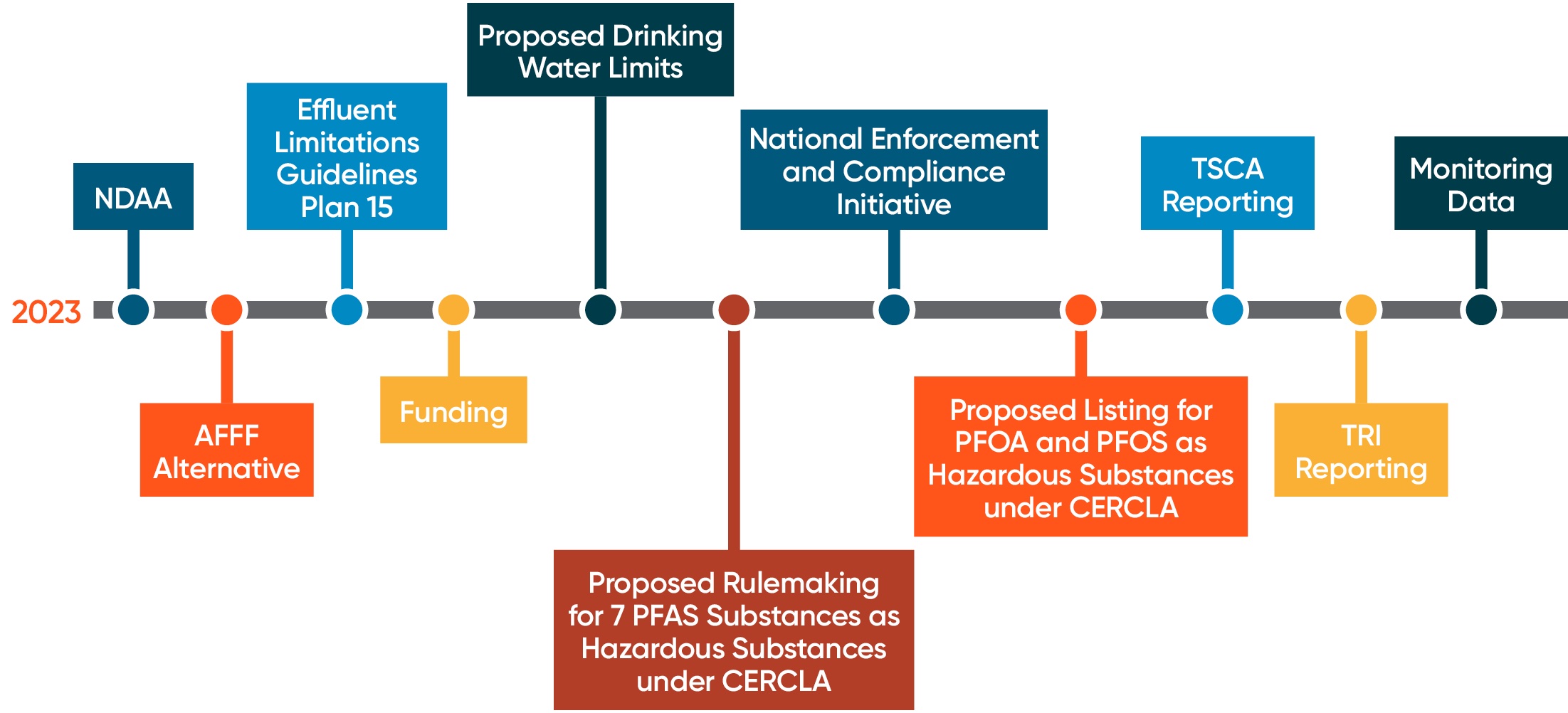

Feb 07, 2024As expected, 2023 was an expansive year for the regulation of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (“PFAS”) at the federal level. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) took (or at least proposed) significant actions under a range of different regulatory programs and environmental statutes including the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (“CERCLA”), the Toxic Substances Control Act (“TSCA”), the Safe Drinking Water Act ("SDWA"), the Clean Water Act (“CWA”), and the Toxics Release Inventory (“TRI”) Program. That noted, there were two significant absences from the list of new regulations and actions taken by EPA in 2023 that we discuss below: (1) finalizing the drinking water limitations for six PFAS substances; and (2) formally designating PFOA and PFOS as “Hazardous Substances” under CERCLA.

While not intended to be a complete list, the following is an overview of the key developments in 2023. Many of the key developments were highlighted in EPA’s December 2023 PFAS Strategic Roadmap: Second Annual Progress Report, and the White House Council’s March 2023 White House Council on Environmental Quality Document.

Drinking Water Actions

Drinking water impacts from PFAS have been a major driver for regulatory action at both the state and federal levels over the past few years, and 2023 was no exception.

Proposed Drinking Water Limits

Perhaps one of the most notable actions was EPA issuing its proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (“MCLs”) and Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (“MCLGs”) for six PFAS compounds. More information on the specifics of the proposed MCLs is available in BCLP’s client alert, but the proposed MCLs and MCLGs are as follows:

- PFOA: MCL 4.0 parts per trillion (“ppt”) and MCLG zero;

- PFOS:

MCL 4.0 ppt and MCLG zero; and

- PFNA, PFHxS, PFBS, and HFPO-DA (or GenX Chemicals): MCL and MCLG 1.0 on the Hazard Index (unitless).

The concentration limits in the MCLs are extremely low and the MCLGs are even lower, and EPA has suggested that it will continue to lower the MCLs over time as test methods improve to try to reach the MCLGs. Interestingly, EPA has yet to issue the final MCLs, despite announcing that it would do so before the end of 2023. It is unclear at this point whether EPA will issue the MCLs in 2024. If that happens, these limits will be legally enforceable, and will apply to many public water systems (“PWS”) that provide drinking water across the country, providing a very stringent, but uniform, drinking water limit for these compounds.

Funding

EPA announced that $2 billion dollars was available through grant programs to people in disadvantaged communities to address emerging contaminants, including PFAS, in drinking water across the United States. Assisting both states and territories, this funding is designed to help people in “small, rural, and disadvantaged communities.” This outreach is part of EPA’s larger effort to assist people who are dealing with emerging contaminants in their local economies. At this time, it is unclear how the money will specifically be utilized in these areas once it is allocated.

Monitoring data

EPA released the second set of data from the latest Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (“UCMR 5”) for PWS. UCMR 5 covers 30 chemical substances, 29 of which are PFAS compounds. Most PWS are required to sample for the 30 compounds between 2023 and 2025, and according to EPA, “UCMR 5 will provide new data that is critically needed to improve EPA’s understanding of the frequency that 29 PFAS (and lithium) are found in the nation’s drinking water systems and at what levels.” Thus far the data collected from 13.6% of PWS has shown detections, including PFOA and PFOS being measured above the EPA Health Advisory levels in 9.5% and 10.7% of PWSs, respectively. PWS have already raised concerns about the testing costs and the limited availability of qualified testing labs, but compliance with UCMR 5 will continue to be a burden for regulated PWS entities through 2025.

CERCLA and Site Screening

CERCLA Hazardous Substances Designation

In September of 2022, EPA proposed listing PFOA and PFOS as “Hazardous Substances” under CERCLA. As discussed in BCLP’s client alert, the listing will have substantial implications for EPA site cleanups and the potential reopeners of closed remediation sites. Further, it will create significant ripple effects that will impact due diligence requirements, cost recovery litigation, and state regulatory obligations that are tied to the CERCLA list of Hazardous Substances. EPA received a voluminous number of public comments in response to this proposed rule, and as a result, the formal listing has been delayed until March 2024, and possibly longer.

EPA also issued an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking last year to designate seven additional PFAS compounds (in addition to PFOA and PFOS) as Hazardous Substances under CERCLA: PFBS, PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO–DA or GenX, PFBA, PFHxA, and PFDA. The notice also raised the possibility of listing precursors to PFOA, PFOS, and the seven listed PFAS compounds, as well as “Categories of PFAS,” either of which could introduce many other PFAS substances into the Hazardous Substances designation. At this time, it is unclear which, if any, of the listed PFAS compounds or categories of compounds from the notice will be included in the anticipated listing for PFOA and PFOS. For additional information, BCLP published a client alert providing details regarding this action.

Site Screening

With respect to site screening, EPA significantly expanded the Regional Screening Levels (“RSLs”) - used for risk-based screening at potentially impacted sites - to include numerous PFAS substances. The RSLs are not binding concentration limits or cleanup standards, but rather they are used by EPA to evaluate whether a potentially impacted site warrants further investigation. The inclusion of RSLs for PFAS further reinforces EPA’s stated goal of investigating and ultimately remediating PFAS impacts as part of site cleanup actions.

TSCA and TRI Reporting

TSCA Reporting

In perhaps the most significant rule issued in 2023 in terms of impacts to the business community, EPA issued a final rule imposing new PFAS reporting requirement under TSCA. As discussed in more detail in BCLP’s client alert, manufacturers, including importers, are required to report certain categories of PFAS compounds that were manufactured within the United States or imported into the United States between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2022. Unlike many prior TSCA rules, articles are not exempt from the requirements of the rule, which means that businesses that imported articles that contain PFAS compounds during the reporting period (e.g., consumer products which contain PFAS) may have a reporting obligation. The reporting window opens on November 13, 2024, and all reports (other than for small businesses) must be submitted by May 8, 2025 (see §705.20 of the rule).

The required information is quite extensive. As a result, if you have not done so already, BCLP strongly encourages you to evaluate if this reporting rule applies to your business.

TRI Reporting

The TRI Program is one of the primary ways that many companies are required to report their chemical usage. The National Defense Authorization Act added 160 PFAS compounds to the TRI list in 2020, and EPA subsequently added nine (9) additional PFAS substances in 2023, making a total of 189 PFAS substances that are included in the TRI Program at the end of 2023, although that number has recently grown to 196 total PFAS substances.

Until 2023, the PFAS compounds on the TRI list were subject to certain exemptions, and specifically, the de minimis exemption. As discussed in a BCLP client alert, EPA reclassified the PFAS compounds on the TRI list as “chemicals of special concern,” which eliminated the de minimis exemption. Practically speaking, this means that businesses must account for even small concentrations of PFAS compounds when evaluating their TRI reporting obligations. This action underscores the recent efforts of EPA to significantly increase reporting requirements for all PFAS substances, regardless of the amount.

Miscellaneous Actions Addressing PFAS: Enforcement Initiatives; Funding; and Additional Guidance

National Enforcement and Compliance Initiative

EPA included “Addressing Exposure to PFAS” as one of its six National Enforcement Compliance Initiatives for 2024-2027. According to EPA, this initiative will “hold responsible those who manufactured PFAS and/or used PFAS in the manufacturing process, federal facilities that released PFAS, and other industrial parties who significantly contributed to the release of PFAS into the environment.”

Effluent Limitations Guidelines Plan 15

The Final Effluent Guidelines Program Plan 15 (“ELGs” or “Plan 15”) was finalized. ELGs are national industry-specific wastewater regulations based on the performance of demonstrated wastewater treatment technologies. The CWA directs EPA to promulgate technology-based ELGs that effectively reduce pollutants using available treatment technologies. According to EPA, “revised ELGs and pretreatment standards are warranted for reducing PFAS in leachate discharges from landfills [and] Plan 15 also announced an expansion of the ongoing study of PFAS discharges from textile manufacturers and a new study of POTW influents to publicly owned treatment works.”

NDAA

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 (“NDAA”) provided $20 million dollars for the armed services to extend the authorization to conduct an ongoing human health assessment related to contaminated sources of drinking water from PFAS substances (Pg. 16). Additionally, the NDAA states that on October 1, 2025, the Secretary of Defense may not execute any contract for the purchase of firefighting personal protective equipment (“PPE”) if the PPE contains a PFAS substance (Sec. 343).

AFFF Alternative

In a related development, the Department of Defense (“DOD”) has approved a viable fire-fighting alternative to Aqueous Film Forming Foam (“AFFF”) called F3 MILSPEC. Historically, AFFF has been the firefighting foam predominately used by the DOD and other entities for fire suppression, especially at airports. The approval and use of one or more alternatives will reduce the on-going use as AFFF as a fire suppressant.

Conclusion

As should be apparent from the many actions described above, EPA has continued to focus heavily on regulating PFAS compounds in a variety of environmental media and under different regulatory programs. Businesses that historically or currently interact with these compounds should consider identifying and evaluating their potential risk and reporting obligations. BCLP will continue to monitor and report on PFAS-related government actions at both the federal and state levels throughout 2024, when we expect to see further significant developments in the regulation of PFAS.

For more information on PFAS chemicals, and the regulatory and litigation risks that they pose, please visit our PFAS webpage. If you have a question about how to manage federal PFAS risk, or in any specific state jurisdiction, please contact Tom Lee, Bryan Keyt, Erin Brooks, John Kindschuh, or any other member of our PFAS team at BCLP.

Related Practice Areas

-

PFAS Team